• Shutters close on drinking den favoured by presidents, revolutionaries and artists

Jo Tuckman in Mexico City

Monday February 18 2008

Mexico City's oldest licensed bar stands on a corner of the grand Zócalo plaza. Across the road is the huge National Palace, home of Mexican presidents until the 1930s and still the official seat of executive power. Behind lie the ruins of the great Aztec capital, to one side looms the Metropolitan cathedral, and in every available open space is the buzzing, often chaotic street life of the historic centre.

But while those other Mexico City landmarks will live on, the doors to El Nivel have closed, taking with them a small piece of history.

"Every big city has a sort of an iconic place. There's La Fleur in Paris, or the Chelsea hotel in New York, or the French House in Soho. This was a cantina that had a presence and a fullness that you very seldom find," said Irish-born artist Phil Kelly, who discovered the bar after moving to the Mexican capital in 1982.

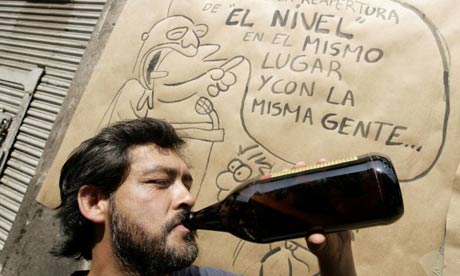

The closure of El Nivel, frequented over the years by artists, writers, revolutionaries, presidents and street vendors, has provoked a passionate protest from its regulars. Kelly was among the hundred-odd demonstrators who gathered outside El Nivel last month to drink beer and chant their outrage at the shutters that have stayed down since January 2.

The reason for the closure is unclear. The owner, Ruben Aguirre, has blamed the country's biggest university for pursuing a court case to take over the building housing the bar. The National Autonomous University says this is a separate issue and that Aguirre has hidden motives for shutting up shop.

But the protesters didn't seem to care who was to blame - they just wanted their bar back. "Nivel sit tight, we're all in your fight," chanted some, as others posted signs proclaiming it "cultural and alcoholic patrimony of the nation".

"Why do people have to have huge monuments?" complained Kelly. "There can be little monuments too, you know - ones you don't have to worship."

Called El Nivel (The Level) because the building was used to measure the height of the floods that plagued the city, the bar holds the licence number 001, issued in 1855. That was the last year of the presidency of Antonio López de Santa Anna, who ruled Mexico 11 separate times in the turbulent post-independence decades, and who was, some say, one of El Nivel's first customers.

Benito Juárez, Mexico's liberator from French occupation later in the century, also reputedly drank at the bar, as did Carlos Salinas, the president who negotiated the North American Free Trade agreement in 1994, and then became the nation's favourite political hate figure. Then there were the revolutionaries: Mexico's own in 1910, followed in the 1950s by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. A steady stream of intellectuals, writers and artists pushed through the wooden swing doors. But, the legend goes, none received treatment any different from the regulars who worked on the streets nearby and would duck out of the chaos for a beer.

It was this ability to remain unpretentious and non-elitist in a country riven by inequality that made it so special for some. "We may not be able to defend our torn-up country," said Beatriz Russek, as she sipped her beer on the pavement outside. "But at least we can defend our cantina."

Fuente: The Guardian (UK)

Audio

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario